By Paul Benedikt Glatz, Jeremy Kuzmarov and Steve Brown

From Covert Action Magazine | Original Article

Collusion by the White House, the Pentagon, and the mainstream media resulted in disparagement, denial, and suppression of eyewitness testimony confirming that most POWs were actually well-treated by their North Vietnamese captors (in contrast to the brutal torture and death often meted out to North Vietnamese POWs by U.S. forces).

When numerous U.S. POWs began to understand the truth about the war they had been fighting, they spoke out against it—voluntarily—as an act of conscience. But they were cynically portrayed as traitors, turncoats and “camp rats,” their reputations and lives destroyed, driving many to despair and even suicide.

Among the few memories that most Americans still retain of the Vietnam War—now nearly 60 years in the past—one of the most vivid centers around the torture suffered by Senator John McCain at the hands of his brutal Vietnamese captors while a prisoner of war in Hanoi’s Hoa Lo prison (AKA The Hanoi Hilton).

This story has been told, retold, and continually burnished countless times by admiring media interviews and a flood of books and memoirs, including several by McCain himself.

Another memory of the war, still believed by millions of Americans, is that hundreds or even thousands of American soldiers classified as MIA (Missing in Action) are actually being held and tortured in secret North Vietnamese POW camps, callously abandoned by our government and desperately praying to be rescued—preferably in a Hollywood-style rescue by Chuck Norris or Sylvester Stallone, who starred in the spate of Commie-hating blockbuster movies inspired by their plight.

This belief is continually reinforced by POW/MIA flags which fly at every post office, and a ready supply of new books and movies, such as the 2018 release of the film M.I.A. A Greater Evil.

But both memories of the Vietnam War are false memories. However passionately believed, they were cynically manufactured fantasies implanted in all-too-willing American minds for political purposes.

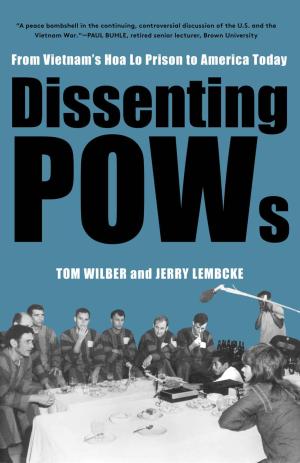

How and why these counter-factual beliefs were so successfully foisted on the American public is the subject of the new myth-shattering book by Tom Wilber and Jerry Lembcke, Dissenting POWs: From Vietnam’s Hoa Lo Prison to America Today (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2021).

Wilber is the son of a dissenting POW, Walter “Gene” Wilber, who is featured in the book, and has contributed to the award-winning documentary film The Flower Pot Story by Ng?c D?ng. Lembcke is a distinguished sociologist from College of the Holy Cross who has written a number of books debunking popular myths about the Vietnam War.

The two start their book by noting that the dominant war hero image of the POW—who endured torture and resisted service to enemy propaganda—was to a large extent created by high-ranking men like McCain who were captured early in the conflict.

McCain’s oft-told story of ill-treatment and torture is contradicted by Nguyen Tien Tran, the chief prison guard of the jail in which McCain was held. In a report by The Guardian, “[Tran] acknowledged that conditions in the prison were ‘tough, though not inhuman’. But, he added: ‘We never tortured McCain. On the contrary, we saved his life, curing him with extremely valuable medicines that at times were not available to our own wounded’. . . . [H]e denied torturing him, saying it was his mission to ensure that McCain survived. As the son of the US naval commander in Vietnam, he offered a potential valuable propaganda weapon.”

Most of the others promoting a heroized image of U.S. POW’s were graduates of service academies and came from privileged backgrounds. They included a) James Stockdale, who ran for Vice President in 1992 as the running mate of Ross Perot; b) Robinson Risner, a double recipient of the Air Force Cross, the second highest military decoration for valor; and c) Jeremiah Denton, who went on to become the first Republican Senator from the state of Alabama and a close ally of President Ronald Reagan.

John McCain fit well with this group because he was also academically privileged and his family included high-ranking military officers like his father, Jack, who was an admiral and the Commander of the U.S. Pacific Command.

With post-war military careers at stake, these high-ranking officers played up the alleged barbarity of the North Vietnamese, demanded resistance to interrogations from other captives, and threatened so-called deviants with disciplinary charges after release to the U.S.

The Nixon administration advanced their credibility and status in a desperate ploy to stir up support at home for an unpopular conflict abroad; and further concocted a story—announced in a press conference by Defense Secretary Melvin Laird on May 19, 1969—that 1,300 American soldiers deemed “missing in action” were believed to be prisoners of war.

The unaccounted for would now publicly be described as “POW/MIA,” implying that any serviceperson missing in Vietnam could also be a prisoner of war. This transformed the war from a political issue into a humanitarian one, trading public support for sympathy. It didn’t matter why we were there in the first place: Our boys were there, and by God were we going to do anything to get them home.

Suddenly, the public image of Vietnam looked very different. The very real footage of brutalized Vietnamese bodies, wailing children, and napalmed villages was traded for a fantasy—all of the violence that had been done in Uncle Sam’s name was now being done to him.

The POW issue soon became a cause célèbre. In the early 1970s, millions of “POW bracelets” were sold by a student group called VIVA (Voices in Vital America), each branded with the name of a missing American serviceman.

These shiny nickel bracelets were spotted on the wrists of celebrities like Sonny and Cher—who had often before dressed like hippies—and Sammy Davis, Jr, and allegedly Princess Grace of Monaco put in an order for two bracelets.

The silver bracelets could even be spotted on the fashion runway, where models with an interest in political activism took to wearing them. A New York Times profile from the day quotes a model named Astrida Woods, who said she was “dissatisfied” with her life as a model and felt the urge to give back. “I began to do some work with Ralph Nader, and now [wearing the bracelets]. It’s a way to contribute something.”

Many U.S. GIs and pilots, however, reported being humanely treated during their captivity, with access to adequate food, recreation facilities and reading material.

Wilber and Lembcke conclude that “instances of brutal treatment” were “less common than [has been] purported” and that evidence of systematic torture drawn from visitor reports, POW statements, and oral histories was scant.

Those POWs who questioned the war were dismissed by the military for their supposedly “weak personal character” and “lack of education and backgrounds in broken and poor families,” a typical case of “psychologizing the political.”

These men were in turn stigmatized and then forgotten by the public amidst the manufactured concern about POW/MIAs who were supposedly brutalized and then kept in captivity and abandoned by their government.

Camp Rats?

The ranks of the POW dissenters included Lt. Col. Edison Miller, a recipient of the Distinguished Flying Cross and Purple Heart from California who spent six years in captivity after his fighter plane was shot down over North Vietnamese skies on October 13, 1967.

A contemporary described Miller, a Californian who flew previously over Korea, as a “first-rate pilot with a zeal for combat but an independent sort.”

John McCain falsely accused Miller of being a turncoat because he appeared in North Vietnamese propaganda.

In his 1999 best-selling book Faith of My Fathers, McCain wrote about Miller as one of two “camp rats”—the other being Tom’s father Gene, who had been executive officer of a squadron of F-4s when he was shot down over North Vietnam on June 16, 1968.

McCain said both “had lost their faith completely.”

“They not only stopped resisting but apparently crossed a line no other prisoner I knew had even approached,” McCain wrote. “They were collaborators, actively aiding the enemy.”

Miller told the Orange County Register in response to these charges that McCain had “lied about me … The attacks on my character and integrity are totally without merit or justification. I did stand up and say the war was wrong. I would speak against the war, but I never spoke against my country. And I gave up no secrets.”

McCain accused Miller of receiving eggs, bananas and other delicacies to eat from camp guards. Miller says, however, that he never saw eggs during his internment and that McCain was never in a position to see the food brought to him.

McCain further claimed that Miller turned him into a North Vietnamese guard when McCain tried to befriend him, and that the guard then beat McCain. Miller said: “I never ratted out a fellow American. McCain has fabricated and exaggerated his experience for political advantage.”

Miller’s anti-war views had been sharpened in conversation with Navy Commander Robert Schweitzer, a captive from 1968 to 1973 who died a year after his release while still on active duty in San Francisco.

Schweitzer felt that, because the U.S. had never declared war, there could not legally be any North Vietnamese prisoners of war, only “Americans detained by a foreign power,” Miller said.

A tape of a conversation between Miller and Schweitzer was played for other prisoners, who heard not only an anti-war message but a challenge to the legality of the U.S. military action in Vietnam.

In 1970, when Miller and Gene Wilber were interviewed on national television, Wilber called for an immediate U.S. troop withdrawal “so that the Vietnamese can solve their own problems.”

U.S. journalists at the time, however, did not take their interview seriously, regarding it rather as a North Vietnamese propaganda show.

The two men along with Schweitzer continued to write protest statements and together with fellow dissenters met with American peace activists visiting North Vietnam, including actress Jane Fonda and former U.S. Attorney General Ramsey Clark.

Empathy for the War’s Victims

Most dissenting POWs came from a working-class background.

James A. Daly, an African-American infantryman from the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn, for example, was raised in poverty by a single mother.

His 1975 book, Black Prisoner of War, describes his three years of jungle confinement after his capture by North Vietnamese soldiers and the South Vietnam-based National Liberation Front (NLF), followed by a two-month trek north to Hanoi on the Ho Chi Minh trail where he experienced what it was like to be on the receiving end of U.S. ordnance.

Bob Chenoweth, from a white working-class family in Oregon, similarly developed an empathy for the Vietnamese people and a distaste for the racist views of most Americans toward the Vietnamese.

A helicopter crew member, before he was shot down and captured, Chenoweth said he “couldn’t see how U.S. forces could possibly be helping the Vietnamese given the attitude that GIs had, viewing them as ‘subhuman’ and disparaging them as ‘gooks and dinks.’”

Chenoweth and other of his contemporaries authored anti-war statements, wrote messages to GIs asking them to follow their consciences, sent letters to politicians, and recorded tapes to be aired via Radio Hanoi.

Higher ranking POWs responded by trying to isolate the dissenters from other American prisoners while charging them with participating in a conspiracy against the United States.

One of the dissidents, Abel Kavanaugh, committed suicide as a result of the intense pressure and prospective stigma of a dishonorable discharge only a few months after coming home from Vietnam.

Charges against the POW dissidents were eventually dropped, Wilber and Lembcke believe, so as to not jeopardize the hero-prisoner story with too much attention on dissent and through a possible exposure of inconsistencies in the accusers’ own prison biographies.

Fear of Communist Infiltration

A critical trope in Cold War America was the fear of communist infiltration and internal subversion through brainwashing and mind control.

This trope was fortified by a CIA propaganda effort that depicted Korean War POWs who defected to the North Korean and Chinese side as having been brainwashed in interrogation.

Most of these defectors were in fact African-Americans who did not want to return to the Jim Crow South, while others were attracted by communist ideals or saw the U.S. war as immoral.[1]

The stereotype of the brainwashed POW of the Korean War turned collaborator and traitor because of his weak character would become the backdrop for the discrediting of the dissident POWs of the Vietnam War.

In an appearance on CBS’s 60 Minutes, Gene Wilber was grilled on whether he had given in to the enemy to make antiwar statements. That he had acted on his own “conscience and morality” was drowned out by host Mike Wallace’s implications of collaboration and opportunism.

When he was subsequently invited to the White House POW reception, Wilber found his hotel room broken into and marked with accusations of treason when he returned from the reception.

In the summer of 1973, James Stockdale charged Wilber and Edison Miller with collaborating with the enemy, mutiny, and inciting personnel to insubordination. However, military judges found insufficient evidence to prosecute the case, and Wilber and Miller instead received letters of censure for their failure to meet the standard expected of officers.

Hollywood Revisionism

POW films starting from this time focused on returnees’ estrangement with their families and society and were told as stories of spousal infidelity, representing both individual drama as well as a sense of “home-front betrayal.”

These films were part of a post-war revisionism, which included a spate of films that contributed to the legend of American servicemen left behind in Vietnam.

In the 1980s, a new subgenre emerged focused on Vietnam veterans heroically taking on the task of returning to Indochina and liberating the left-behind POWs, who had been betrayed on the home front and abandoned by the U.S. government.

The POWs were depicted as victimized and emasculated captives who needed to be rescued by individualist heroes and whose honor as Americans was to be restored.

This image, Wilber and Lembcke argue, fits the post-war efforts to psychologize the once political conflicts of the Vietnam War and to depict the veteran as a victim and loser.

More of a heroized image and the POWs’ endurance of torture was revived with the 1987 film, The Hanoi Hilton, which starred Michael Moriarty, Ken Wright and Paul Le Mat as U.S. POWs who defy their captors while enduring brutal treatment at Hanoi’s Hoa Lo prison (aka The Hanoi Hilton).

This film meshed particularly well President’s Ronald Reagan’s characterization of the Vietnam War as a “noble cause,” fought by noble men, with the POW dissenters by implication being ignoble.

Persistence of the Hero-Prisoner Story

In their quest to comprehend the persistence of the hero-prisoner story, Wilber and Lembcke take their readers back to American colonial history and the captivity narratives emerging during that time.

These stories are about a complex mix of violence against captives, temptations to stay with their captors, the ideal to remain loyal with their fellow colonists, and their Christian beliefs.

Such tensions and correlations between the Self and the Other were critical in the making of an American identity. The wars in Korea and Vietnam and the POW experiences there can be understood as a new chapter of this identity-making process. Here, too, Americans must prove their will and ability to endure the brutality of a racialized Other.

A wrench in the story, however, is revealed in the autobiographical accounts of POW-heroes like Stockdale, Denton, and Risner. They wrote about fasting as a way of enforcing self-discipline and self-assurance, sometimes with a religious subtext.

More bizarrely, they also wrote about self-mutilation—the deliberate infliction of physical wounds on themselves that would be visible during filmed interviews.

The aim was to make it appear to other POWs (and to the U.S. public) that they had been tortured. One officer wrote of how he purposely damaged his vocal apparatus so he could not be forced to make propaganda statements.

In addition to some high-ranking officers attempting to portray themselves as heroes by means of self-mutilation, Wilber and Lembcke also noted that they tried to keep political literature and news of dissent back home away from other POWs, fearing that these would enhance critical positions on the war and against their authority within the prison population.

Moreover, these ranking officers often despised the more humane view of the Vietnamese displayed by other prisoners, including an interest in their language and culture, and an understanding of why they were fighting back against an invasion of their country by the most powerful military force in the world.

Bringing Back Forgotten Dissenters

Wilber and Lembcke’s book helps restore these forgotten POW dissenters to their rightful—and honored—place among the large and diverse Vietnam generation of dissidents, draft resisters, oppositional GIs, veteran activists, deserters, and all those who supported them.

The book also shows that, despite all destruction and death brought by the invaders from the sky, North Vietnam maintained a moral superiority through oftentimes fair treatment of the captured Americans. This was in stark contrast to the more systematic adoption of torture methods by USAID and CIA-trained police under the Operation Phoenix and like-minded programs.

The POW/MIA flag that flies today over the White House is intended to honor the men who endured captivity; however, it continues to perpetuate a distorted understanding of a war that was as abominable as it was unjust, and helps to advance a dangerous nationalist ideology that will lead to future Vietnams.

- See Clarence Adams, An American Dream: The Life of an African American Soldier and POW Who Spent Twelve Years in Communist China (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2007). ?