Ethan McCord on tour in California speaking in the evening at Revolution Books in Los Angeles, after visiting several high schools in the Orange County area.

Collateral Murder: Ethan McCord in LA from marshall blesofsky on Vimeo.

Local news coverage at www.randomLengthsNews.com

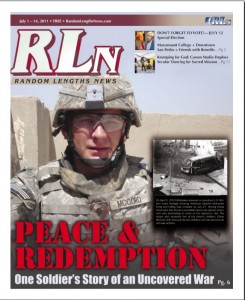

Peace and Redemption: One Soldier’s Story of an Uncovered War

By Zamná Ávila, Assistant Editor

More than a year ago, Random Lengths News published “The Uncovered War: The Untold Story of the Iraq War,” a discussion about the then-recent posting of a July 2007 Apache-helicopter a shooting in Iraq that killed 12 people and wounded two children on Wikileaks.org. The story described some the of events in the controversial footage, the fundamental issues that led to the incident and the wider impact on soldiers and people in Iraq.

As part of a two-part series, this issue of Random Lengths News brings readers the story of Ethan McCord, the soldier who rescued the two wounded children. The driver, the children’s father, was fired on by the U.S. helicopter and killed while attempting to help Reuters photographers Namir Noor-Eldeen and Saeed Chmagh. These days, McCord actively speaks against the war. The Wichita, Kan. man, originally from the Bay Area, recently visited seven Southern California schools, including San Pedro High School, where he shared his story. Ethan McCord’s antiwar activism, when paired with his record as a proud serviceman and a family with a long military tradition, can seem like an oxymoron until you understand the psychological toll of war making.

As with many U.S. soldiers, Ethan McCord answered the call of duty after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001 on U.S. soil. He worked at a retail store as a manger at the time of the attacks. Reared in a conservative family, whose military history dates back to the Revolutionary War, his patriotism and decision to enlist was not surprising. “We were taught that joining the military and being a soldier is very admirable,” said McCord, who then was 25 years old. “I ran out and signed up right after Sept. 11. I remember being angry and emotionally hurt that someone would attack us. This great country, the United States of America that is out there always providing these freedoms and democracies for people.

“We strive to be the best that we are and here are these Muslim extremists who are running out

attacking us and who hate us for our freedoms.” At first, McCord joined the Navy where he was a supply man, handing out uniforms, procurements, placing orders, among other clerical-type duties. After four years, he asked for a conditional release from the Navy to join the Army, a type of lateral transfer. “I felt like I wasn’t doing enough,” he said. “I wanted to be the guy kicking down doors and shooting Muslims and killing them.” But he soon came to find out that his views of reality were distorted.

“I get into the Army and I see that the Army is run more like the mafia: ‘You mess up and we are

going to wack you’ type… (there was) an emphasis on killing people more so than the Navy was,”

he said. “As soon as basic training hit, it was very in your face, ‘kill, kill, kill!”

The gruesomeness of some of the Army infantry marching cadences—traditional call-and-response

work songs sung by military personnel while running or marching—stuck with McCord, including verses such as: “What makes the green grass grow? Blood, blood, blood of our enemies,” or “I went to the market where all the Haji shop, pulled out a machete and I began to chop. I went to the playground where the Haji children play, pulled out a hand grenade and blew them all away.”

“It was all meant to dehumanize our enemies,” McCord explained. “Racism was used in the military,

it was extremely rampant.” Being older than most of the new recruits, McCord, then 29, believed that the cadences were a way to break people down and build them back up, but he hoped that it would change when he formed into his unit. It didn’t change. “I didn’t have a very big grasp on what was going on in Iraq,” he said. “I thought we were just killing enemies over in Iraq.”

McCord remembered growing up watching videos of soldiers of World War II, where American soldiers, who helped free the French, were greeted by women kissing and throwing flowers at them. He fantasized about having a similar experience in Iraq. But that fantasy ended quickly.

“When I got over there, instead of flowers being thrown at me there were rocks being thrown at me; instead of kisses I was getting the middle finger; and I was getting shot at and blown up on a daily basis,” he said. “I couldn’t understand for the life of me why the Iraqis hated us so much when we first got there.”

He quickly discovered the reason Iraqis hated the American soldiers: the soldiers were killing them.

“We were shooting innocent people; we were getting orders to shoot indiscriminately at people,” he said. “If we felt threatened, we were able to engage that person and a lot of soldiers who went over, were told that ‘All the training leads up to your [being a] killer and your job is to go over and kill.’ And, soldiers would get so hyped up about being able to kill somebody they’d just start killing people… These kids were really good kids turned into monsters, in a sense.”

McCord describes a form of anger that developed among many soldiers directed at American civilians back

home who they perceived wanted the soldiers in war. He said most missions consisted of soldiers driving around, waiting for someone to engage them, to shoot at them or blow them up so that they could kill the person doing the shooting. He said their battalion commander told them to kill “every mother-fucker in the streets” whenever a road side bomb went off, which he saw happen on several occasions, where men, women and children were killed because an improvised explosive went off.

On more than one occasion, McCord’s unit, Bravo Company 2-16, would dress up with skeleton-printed

masks and gloves that glow in the dark, and go on night raids. In the middle of the night members of his unit would kick in doors and drag men out of their homes and beat them, terrifying the families. He remembers one man in particular, who was dragged out of his home, and was beaten so severely that all his teeth were knocked out, after which the soldiers just left him on the side of the road.

“We wanted to get information out of people and we felt that everybody in Iraq knew something or was the enemy,” he said. While he said he didn’t directly participate in beatings, he stood silent, afraid of the repercussions if he were to speak up. Because he was usually the driver or was on the gun turret, he

was able to fake his participation, even if that meant he’d pull security while others beat civilians. “In basic training you’re taught that you are no longer an individual, you are a part of the unit and the minute you are an individual you are wrong,” he said. “Although me and a few other soldiers refused to do things like fire indiscriminately at human beings, we would still have to give the illusion that we were firing our weapons. So, we’d fire into rooftops of buildings or open fields to provide the illusion that we were participating.”

So, what made McCord so different? Why didn’t he participate in the abuses? McCord said he believes that perhaps it was the fact that he was older and was a parent. Most of the unit soldiers were in their late teens and early 20s, though some of the soldiers who were conscientious objectors were also young.

“I think a lot of it has to do with your upbringing,” he said. “I came from a military family but I also came from an extremely religious family and going back to religion you aren’t supposed to do these things. The teachings of God weren’t to torture and beat the hell out of your enemy; it was to love your enemy.”