From Monthly Review | Original Article

In the latest of our MR Conversations, Tom Wilber and Jerry Lembcke, coauthors of Dissenting POWs: From Vietnam’s Hoa Lo Prison to America Today, sit down for a conversation with two invited guests, Vivian Rothstein and David Zeiger, to discuss the story of American prisoners who dissented against the Vietnam War while in captivity.

The conversation begins with the story of Vivian Rothstein’s participation in a 1967 peace delegation to North Vietnam, and her encounter there with the Americans held at Hoa Lo Prison — the subject of Dissenting POWs. One might think that that delegation’s visit to Hoa Lo Prison, and the dissent expressed by almost half of its POW inmates, would have been so controversial as to gain a fair amount of attention at the time. But if that were the case, someone as deeply engaged in the peace movement as David Zeiger — who was active in the GI Coffeehouse movement and later directed of one of the only films to tell the story of active-duty G.I. resistance against the Vietnam War (“Sir! No Sir!“) — probably would have heard more about it.

A story new to even the most seasoned experts on the Vietnam War…

As soldiers held at Hoa Lo Prison returned from Vietnam in 1973, Americans became riveted by POW coming-home stories. The press circulated legends of heroes who endured torture rather than reveal sensitive military information. News leaks suggested that others had denounced the war in return for favorable treatment.

But what really went on behind the walls of Hoa Lo Prison?

The truth is that the press covered up something quite critical: That U.S. troop opposition to the war was so genuine, and so vast, it even emerged from within the walls of the prisoner of war camp that came to be known as “The Hanoi Hilton.”

Journalists also failed to uncover the existence of a divide between lionized pro-war “hardliners” and anti-war “dissidents” in Hoa Lo. “Dissenting POWs” recovers this history, revealing the suppressed story of the factionalism in Hoa Lo, revealing the class and racial backgrounds of the dissenters, and addressing the points of connection between many of the POWs and those that they were sent to fight.

From the introduction to Dissenting POWs:

“….we pursue a hunch that the tensions between POWs were rooted in the disparate socioeconomic backgrounds of the antagonists. The privileged backgrounds of the SROs were in sharp contrast with the modest origins of war resisters. It’s a hunch triggered by clues scattered by Craig Howes in his 1993 book Voices of the Vietnam POWs, and reinforced in Milton Bates’s 1996 The Wars We Took to Vietnam. We use newly available biographical and oral history material to show that class disparities extended into the SRO ranks. Objections to the war voiced by two of the most senior officers, Gene Wilber and Edison Miller, got them banished by their peers. Just as “class” designates an objective social position with implications for wealth and income and values derived from its material realities, it also connotes the subjective evaluations that members of one class make of others. Modifiers like “upper” and “lower” class imply character and even moral judgments that are then arranged, even if unwittingly, into hierarchies for assigning social standing and status.”

….we argue that the public memory of dissenting POWs was lost less to censoring or the demands of the movie market than it was to displacement of their acts of principled courage by images of them as victims of the war. Casting POW dissenters as sadsack losers precluded their inclusion in the great American captivity narrative at the center of the nation’s founding mythology, wherein the captive- hero remains a prisoner at war, loyal to the mission on which he was sent. The antiwar Vietnam POWs would be the antiheroes in, say, the legend of John Smith and his resolve in the face of torture and the temptations of Pocahontas—the weakling POWs had no place in the American story, no association with traditions out of which memories could have been constructed.

…The banishment of POW dissent from memory leaves a void in American political culture where new generations of uniformed war resisters will look for role models, and civilian activists will look for allies in their efforts to end U.S. wars of aggression. Filling that void is the mission of this book.

From Chapter 3 of Dissenting POWs:

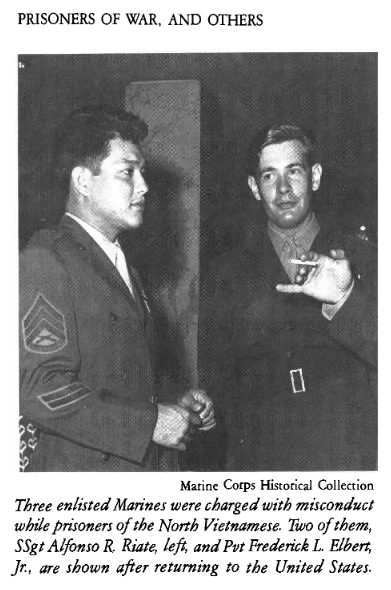

Alfonso Riate and his fellow dissident POWs (to whom the book is dedicated, alongside Bob Chenoweth)

If the Damned Eight story was to be made into a film, the trailer for it would feature Alfonso Riate. Riate was born in Sebastopol, California. His dad was Filipino and died when Al was very young. His mom was Native American from the Karuk tribe. She was famous as a tribal elder and teacher of the tribe’s language. Riate’s granddad practiced Indian traditional medicine. Al and his younger brother John eventually moved to Los Angeles where they lived alone. Al forged papers so they could go to high school.

Chenoweth remembered meeting Riate at Portholes:

I both admired and respected him right from the start. We got to that camp sometime in April 1968. The camp was a microcosm of life back home. When our group came [into Portholes], including Rayford, we quickly divided up along “race lines” (for lack of a better term). I had a long hatred for racist bullshit that went back to my high school days. Rayford and I talked about race, slavery, and the like since we were next to each other.

I can tell you that Al had a very hard early life, but I know it was not a life without love. Reservation life, and all its hardship and injustice and racism, is not widely understood by “white America,” even today. In the 50s and 60s it was brutal. Al’s decision to leave the reservation for LA with his brother showed both strength and courage.

After high school, Riate took classes at Long Beach Community College and joined the Marines in 1965. He volunteered for duty in Vietnam and went to K company, 3rd Battalion, 3rd Marine Division (K-3-3). He was captured while on an operation near Hill 861 in Quang Tri Province.

Al once tried to escape from Portholes. His Filipino-Indian ancestry gave him a dark complexion—and the best chance that any of us could be mistaken for a Vietnamese. He had also learned a little Vietnamese language. On a work detail out of the camp, he escaped. Two days later, he walked into an NVA anti-aircraft site, sat down for tea with the soldiers! One of [the NVA] went off shortly after that and after a while the camp guards came down the trail to take him back to camp.

Chenoweth’s lesson from Riate’s attempted getaway was “You can get out of the camp but not out of the country!”

In a screenwriter’s hands, the character of a mixed-race Marine who walked onto an enemy rebase and sat for tea might get embellished as a writer, soldier-poet, and singer-songwriter. But Riate was all of those, too. While captive, he wrote a protest song in Vietnamese and later recorded it.

In April 1972, U.S. B-52 bombers rolled in on Hanoi. In his memoir, Daly remembered feeling close to the Vietnamese. “All I could picture,” he wrote, “was some man or woman or little kid being shattered to pieces by an American bomb.” During the raid, Daly remembered, Riate had started writing a letter to the prison administrator. When the bombing stopped, Daly and the others gathered around him to read what he had written. The letter acknowledged that the antiwar statements the PCs had been making up to that point were not enough to help end the war. Daly remembered the rest of the letter:

[Riate] wanted to do more than that, he was even ready to consider joining the North Vietnamese Army. . . . For a minute we all just stood there, thinking over Riate’s words. Then Chenoweth and [John] Young asked Riate if they could sign the letter also.

“Well, that’s up to you,” Riate said. “I wrote it as being only from me since I didn’t know if all the rest of you had the same feelings.”

Then, one by one, each of us spoke out on how we felt the same and wanted to sign. My going along didn’t come easily. My emotions were all for it—but it was like a double-edged knife. I think we all found it hard to believe we would even consider bearing arms against the United States.

Colonel Guy, the self-appointed authority figure over the enlisted prisoners, announced the letter-signing to the prison population and threatened that the PCs could be “eliminated” or “liquidated” for their allegiance to Hanoi. The prison camp administration expressed its concern for the safety of the Eight from prisoner-on-prisoner violence through Major Do Xuan Oanh. Xuan Oanh spoke candidly with them about the open situation in Hoa Lo when prisoners were allowed to move about the facility with fewer restrictions after the Peace Accords were signed. The Eight were reassured by the awareness of the prison staff to watch out for them—and keep them safe from their fellow American prisoners.

Riate’s letter would later be the basis for Guy’s charges against the Eight for “conspiracy against the U.S. government.”

….Establishment fears of a mutuality between politicized POWs and the antiwar left were understandable at the time, but two developments mitigated that likelihood. One was that the antiwar movement was feeling the burnout of ten years of hitting the barricades. Splintered by sectarian infighting with a leadership that was rebalancing its political and personal priorities, it was not looking for new fronts to forge. Moreover, and notwithstanding the Hayden and Fonda overtures to POWs, the movement had been as skeptical of the dissident POWs as were the SROs—“How do we know they were not brainwashed?”

A second development was that the psychologizing of the larger population of GI and veteran war resisters was already underway when the POWs returned, and it was proving to be a more useful means of managing their political effectiveness. Why punish behavior that can be discredited, stigmatized as a mental health problem? Why criminalize dissent that can be medicalized? The road to Post-Vietnam Syndrome’s acceptance as the diagnostic category PTSD was already being paved, so why not put the POWs on it along with other Vietnam veterans?

…The history that POWs conscientiously opposed the war before and after their return from Hanoi was not so much erased or suppressed from public memory as it was displaced or overwritten by other, related story lines. The pathologizing of their dissent as a symptom of trauma was the death blow to the sense that POW dissent was conscientious. However, the psychologizing of their protest was itself a refinement of the idea that in-service, veteran, and POW resisters to the wars they were sent to fight had been misled by foreign propaganda, even “brainwashed” by the enemy. It was an idea hatched in the years after the war in Korea to explain why some U.S. POWs made statements denouncing the war, and even considered staying, or opted to stay, with their captors rather than come home when they could.

From Chapter Six of Dissenting POWs:

A people’s narrative is the story they tell about themselves, the story of how and why they came to be what they believe they are. The American story braids together religious and secular themes for a story about the “good people” threatened by powers that could destroy the group from the outside and the weakness of those on the inside who might betray the group. The religious strands of that story are as old as Genesis where Eve is unable to resist the tree of knowledge forbidden to her by God….

As a project begun by Puritans in the seventeenth century, young America was lulled with images of its place in the biblical narrative….The first literature produced by colonial America was the so-called captivity narrative, stories written by Americans about themselves or others who had been captured by Indians. In a 1999 study of that genre, anthropologist Pauline Turner Strong wrote that American identity took form through representations of “struggles in and against the wild: struggles of a collective Self surrounded by a threatening but enticing wilderness, a Self that seeks to domesticate this wilderness as well as the savagery within itself.”

…The captive Self and the captivating Other, as anthropologist Strong puts it, are the oppositional poles between which American identity is formed. That process of identity creation went on well into the nineteenth century as the ongoing conquest of North American Indians reproduced the need of Americans to see goodness in themselves and evil in others. The great and victorious wars of the twentieth century—the war to end all wars, 1917–1918, and the war against fascism, 1941–1945—did not tax that self-identity unduly, but the return of U.S. expansionism in the post–Second World War years did. A crisis of legitimacy that began with the war in Korea grew to dangerous levels during the Vietnam war years, requiring nourishment for the American images of Self and Other.

As if scripted by history, those wars in Vietnam and Korea also produced timely new generations of captives with stories that would reinvigorate the nation’s collective narrative. Perhaps because the war in Vietnam followed so closely on the heels of Korea, it was the former that would make the greater contribution to the captivity literature. The facts of the war’s widely perceived illegitimacy and its loss would, however, cause that narrative to turn inward with an intensity it had never had, spawning a search for the enemy within, and the imagining of that enemy in the absence of the real thing.

The new chapter of the “captive America” narrative that the POW experience of the Vietnam era would write, then, had, like the previous chapters, as much to say about America itself as its enemy….The enduring presence of the terrifying oriental Other in the Vietnam POW story is based less on America’s continuing need to believe the worst about the Vietnamese than on the way that image helps construct what Americans want to think about themselves. Not only are “we” not like “them,” our POWs proved that Americans would not forsake themselves or their nation even under the extreme conditions of imprisonment by the enemy.

****

The SROs’ fear that their underlings might defect, and evidence for the legitimacy of that fear, can be found in the memoirs. By the early 1970s, there was open rebellion against the SRO leadership…..some of the discontent was fomented by the newly arrived POWs from the South who had survived jungle confinement for months and years before arriving in the Hanoi system.

…There was more to antiwar dissent than struggle over the distribution of power among the inmates, but that issue is a clue to understanding the Vietnam-era prisoner experience as an extension of the American captivity narrative. The resistance of rank-and-file POWs and dissident officer-pilots like Wilber and Miller to the control of the SROs, who were committed to their own place in a post-release hero-prisoner script, was accompanied by emotional sentiments that aligned them with the Vietnamese, the enemy Other as seen by hardliners.

It was the humanizing of the Other that the SROs feared because recognition of the humanity in “them” meant recognizing an element of them in “us,” an acknowledgment of the enemy within the hearts and minds of GIs, of Marines, of fellow pilots….”