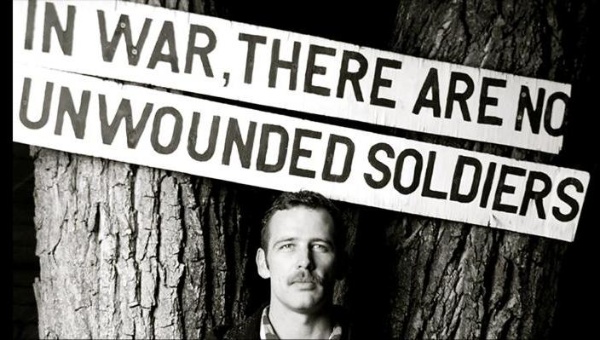

A veteran commits suicide every 65 minutes in the USA, with over 30% of veterans having considered suicide.

By Vince Emanuele | from Information Clearing House

November 07, 2014 “ICH” – “Telesur“- Today, for the second time in less than a month, a veteran in my circle of activist-friends has committed suicide. His name was Ethan. Last month, my friend Jacob, another anti-war veteran, took his life in rural Arkansas. Earlier this year, I lost two members of the platoon I served in; they died of cancer; neither of them smoked or drank. In fact, both Stephen and Sinbad were some of the most straitlaced veterans in our platoon. In the previous three years, two other anti-war veterans died prematurely—Anthony from a drug overdose and Joshua of cancer. As the years roll along, I’m beginning to better understand Plato’s statement on war. I’ve now lost more friends since returning home than I did in the combat-zone. The first time I read Plato’s famous quote, I was thinking about personal struggles, how to remember, or forget, the war, and how to move forward. I didn’t expect my friends to keep dying. But they are vanishing at an astounding pace.

The Center for Public Integrity reports that, “Veterans are killing themselves at more than double the rate of the civilian population with about 49,000 taking their own lives between 2005 and 2011.” To put it another way, a veteran commits suicide every 65 minutes in the USA, with over 30% of veterans having considered suicide. Increasingly, these stories and statistics are making headline news. Many journalists, such as Aaron Glantz, have made it their duty to report on veterans issues. Still, today, most Americans are unaware of the catastrophic consequences of never-ending wars of aggression. And while many stories highlight the plight of veterans, very little is written about the devastating effects the wars have had on the civilian populations who endure such brutality. But that’s expected in a society as introverted as ours. Surely, Americans are blind to the fact that they live in an Empire. In Empires, soldiers, civilians and veterans die, and often.

Personal Struggles

I returned home from my first deployment to Iraq, back in June, 2003. As the war raged on, Americans busied themselves with banal forms of entertainment and mindless politics. There was an anti-war movement, but it was marginal at best and totally impotent at worse. The 2004 Presidential Election was an utter farce. John Kerry, the Democratic candidate that year, stumbled over himself with such ease, it almost seemed as though he was throwing the election for Bush. In fact, Kerry, in many ways, represents the absolute bankruptcy of modern-liberal-ideology. Once a prominent anti-war activist, the Massachusetts Senator quickly switched gears, bootlicking his way to the top of American political society. In the meantime, young GIs fought another endless war abroad, this time in the Middle East.

At the time, I was largely politically ignorant. I grew up in a home filled with Democrats. My father was a union ironworker and my grandfathers were union steelworkers. Many of my cousins, aunts and uncles worked, or still work, in steel mills or manufacturing industries. It was a union home. In some ways, one could say that I grew up class-conscious. My father always told me that rich people ran the show. He told me that cops, judges and lawyers were corrupt and couldn’t be trusted. However his analysis didn’t go much deeper. When I told him I was joining the Marine Corps, he told me that I would end up fighting another senseless war. He reminded me of his friends who came back from Vietnam in the late-1960s, early 1970s, depressed, addicted and violent.

During the summer of 2003, my friends were returning home from their first year at college. Most of them attended state schools, primarily Indiana University. They shared their stories of late-night romps with various sexual partners, drug-induced parties and intellectually stimulating classes. The classes interested me the most, as I had my own drug-induced experiences in the Marine Corps, with plenty of late-night adventures. Perched around our parents’ kitchen tables, we talked about politics, society, art, death and war. Subjectively, their biggest concern was whether or not they were going to pass these classes, graduate and eventually get a decent paying job. My biggest concern was whether or not I’d ever see them again, as our unit was gearing up for a second deployment to Iraq.

Quickly, it became apparent that my journey through life was going to be drastically different from the vast majority of Americans. Now, to be clear, some Americans’ experiences are similar to veterans. For example, young African Americans and Latin Americans living in the most violent American neighborhoods have a good idea what it means to be a veteran, or a victim of war. After all, they’re veterans of a different kind of war: The War on Drugs. Constant news of dead friends, suicides, shootings and drug overdoses plague the discourse in crumbling neighborhoods. The same is true for veterans. Just as most Americans are afraid of the Ghetto, they also shy away from the brutal reality of America’s wars abroad. Both struggles seem too distant, too strange for the average American to comprehend. In some ways, it’s true: Americans who do not live in the Ghetto have no idea what Ghetto entails; and people who have not experienced war cannot comprehend what it’s like to be in war.

Throughout the course of my second deployment, I became increasingly opposed to the war. This happened for many reasons, but primarily because of the insane brutality inflicted on the Iraqi people by my fellow Marines. They took it upon themselves to shoot at innocents, torture civilians and enemy combatants, steal goods from the local populations, mutilate dead bodies, take pictures with corpses and cover-up any evidence of said actions. According to MSNBC, CNN and FoxNews, we were the good guys. Hell, many veterans didn’t even believe such nonsense. But most Americans did. They bought the hype. And the so-called anti-war movement wasn’t much better. Their critique of the war in Iraq wasn’t principled, nor was it serious. If they were serious, they wouldn’t have disappeared once Obama took office. In hindsight, the movement was more of an anti-Bush/Cheney/GOP struggle than it was an anti-war social movement, committed to identifying and confronting militarism throughout American society.

In any case, by the time I returned home from my second tour, it was more than obvious how different my life was going to be. First of all, I was badly addicted to drugs, alcohol and violence. Yes, violence. There is an addictive quality to extreme forms of subjective violence. The act of killing someone is not simply traumatic and brutal, it’s also invigorating and powerful. The drugs and alcohol only staved away my violent urges. If someone didn’t say “thank you” at the supermarket, I thought about the various ways in which I could torture them. When someone at the local gas station wouldn’t hold the door open for the next patron, I fantasized about killing them. Their lack of discipline and manners made me physically ill. Sometimes, when I drove around town, I’d find myself dreaming about a confrontation with someone, anyone. I wanted to show them what war was all about. I wanted to release my anger through violence, often imagining the most gruesome scenarios. Really, I wanted them to feel the same anxiety and anger that I felt during those days. My thinking was shallow: Why should they go through life unscathed by war?

Of course, all of this had a tremendously negative impact on my life. I’ve lost friends, intimate partners and family members due to my personal battles with PTSD. Indeed, I still struggle with these ailments. The nightmares stalk my nightly sleep. Violent urges shadow my daily activities. Each day is a struggle. The more I try and put the war behind me, the more the dog of war bites at my heels as I run away from the grief. One day, my mother asked me to stop smoking in her and my father’s garage. I picked up a garbage can, threw it at the wall and threatened to kill her. Two hours later I was sobbing, head in hands, trying to explain to my friend what happened. He didn’t know what to say. How could he?

Activism as Therapy

I first became involved with the anti-war movement in 2006. The first event I attended was at Valparaiso University. It was a roundtable discussion, with three panelists in favor of the war in Iraq, and three against the occupation. After each participant spoke, they opened the event to a question and answer segment. Listening to people talk about the war made me uncomfortable, even the folks promoting an anti-war message. How could they know? How did they know? Finally, I stood up and said, “I’m a combat veteran who was deployed to Iraq on two separate occasions and I agree with the three panelists who are against the war.” Heads began to turn. People started to whisper. Some in the crowd started to clap their hands. Even the panelists seemed dumbfounded. Three years into the war and it was still out of the ordinary for people on a college campus to hear the opinion of an anti-war veteran. Amazing, indeed.

After the event, a Vietnam veteran came up to me and introduced himself as “Nick.” He continued, “I’m so glad to meet you! Do you realize how important your testimony is going to be to the movement? There’s a couple of veterans I’d like you to meet so come out to our next event.” Nick handed me a flier and we exchanged phone numbers. I remember driving home and thinking about how significant this minor event meant to me. For once, I felt powerful again. I knew that my story, my emotions, my life, mattered. For so many years I had viewed my life as worthless, easily discardable. Suicide was always an option. Homicide was always a fantasy. Now, I had a new commitment: the anti-war movement. I wanted to turn the tide, roll back the negativity and participate in something positive.

Eventually, I linked up with Iraq Veterans Against the War. To me, this was a new beginning. So far, my anti-war feelings had been relegated to poems, music and art. Now I was contributing to an organization that aimed to stop wars, stand in solidarity with the Iraqi and Afghan people, and assist returning veterans with their healthcare and educational benefits. I remember being outlandishly happy about the whole process. I mean, here I am, a working-class kid who barely graduated high school, talking with college-educated activists about ending the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. It was the first time I felt genuine happiness in a long, long time. Plus, the activists were great. Many of the veterans I started to work with had similar stories. They too came from small towns and working-class backgrounds. Unlike my time in the Marine Corps, I felt comfortable in the anti-war community.

I cannot properly recall the amount of organizing workshops, protests, writing workshops, fundraisers, speaking events and street theatre actions we conducted during my first few years with IVAW. But it was a lot of work, both emotionally and physically. Members came and went. Some stuck around for several years. Others are still involved. This work has kept many of us out of jail and alive. For this, I will always be grateful to the anti-war community. It would take weeks for me to name all of the veterans whose lives are better off today due to the work of anti-war activists and community organizers. Where politicians and doctors failed, many of these folks have succeeded. Turns out, many of us simply needed a new mission, a mission dedicated to peace and justice, not war and destruction.

Nonetheless, activism isn’t enough, as time has illustrated. Our activist friends are not immune to suicide. In fact, I would venture to assume activists are more prone to suicide than their non-activist counterparts. It’s difficult to commit one’s self to the world of political activism. Engaging in lengthy conversations about suicide, genocide, ecocide, racism, patriarchy, capitalism, poverty, mass incarceration, etc., is, at times, overwhelming. For me, reading history has helped. I try to remember that I’m a part of a long line of political activists fighting for revolutionary change. I try to remember that I’m a part of a long line of veterans enduring the emotional and physical burdens of war. Throughout the history of Western Civilization, soldiers have fought for imperial interests in far-away lands, only to come home to a farcical society, void of decent values.

Fighting to Live

This year, US citizens have been inundated with stories about suicide, from Phillip Seymour Hoffman to Robin Williams, the topic remains on the tip of every American’s tongue. In the veteran community, suicide is often joked about. The same way that nurses joke about ill patients, or coroners about corpses. Often, the only way to engage with death is to obscure the darkness with a fog of humor. Indeed, comedy often dovetails the absurd. It’s the only way to deal with extreme levels of violence and death. Dark humor, as it’s often called, helps us deal with the emptiness of death. But the jokes only function as a topical ointment. At home, alone, or with loved ones, we’re reminded of this emptiness. It’s an emptiness that will not go away.

At the same time, our efforts are needed now more than ever. The casualties of US wars do not have the luxury of VA hospitals or pro-bono therapy sessions. Victims of US aggression, unlike US veterans and their families, are not awarded preferential medical treatment, educational programs or disability benefits. They live, like so many around the globe, in a constant war-zone. While veterans like myself hope to catch a decent night’s sleep, Iraqis and Afghans are lucky to have a bed to sleep in. This isn’t a “race to the bottom”; it’s simply a recognition of the insanity endured by the primary victims of US aggression. Sure, veterans have it bad. But those we occupied have it much worse. This dynamic must be recognized and confronted in a serious fashion if we ever hope to bridge the gap between justice and absurdity.

Meanwhile, my friends continue to die—my Iraqi friends, my Afghan friends, my Syrian friends, my Libyan friends, my Pakistani friends, my Palestinian friends, my Somalian friends, my veteran friends…