By Lyle Jeremy Rubin

From The Forum | Original Article

Jordan Neely’s killer and the racist violence at the heart of the American imperial project

The man who spent minutes choking Jordan Neely to death on a New York City subway was a United States marine. He enlisted as a private in 2017 and was discharged as a sergeant in 2021.

After his release from police custody—unusual in such a case—he retained the services of a law firm founded by two former officers in the Army National Guard Judge Advocate General’s Corps. Both were deployed to Iraq, where they helped defend soldiers charged under the Uniform Code of Military Justice.

Despite being a defense attorney, one of the firm’s two founders, Thomas Kenniff, ran as the Republican candidate for Manhattan D.A. in 2021 (the same year as his current client’s discharge). He called for “broken windows policing” against petty offenses like graffiti and fare evasion. He was especially keen on reversing bail reform.

Kenniff has said his inspiration for becoming a JAG officer was Tom Cruise’s performance in the true-story-inspired A Few Good Men. In the film, Cruise portrayed the military lawyer responsible for provoking the Guantanamo Bay base commander—played by Jack Nicholson—to admit on the stand that he was behind the extrajudicial, fatal punishment of the recalcitrant marine William Santiago.

These details might strike the reader as random. Perhaps uncanny or evocative. Likely, they raise more questions than they answer.

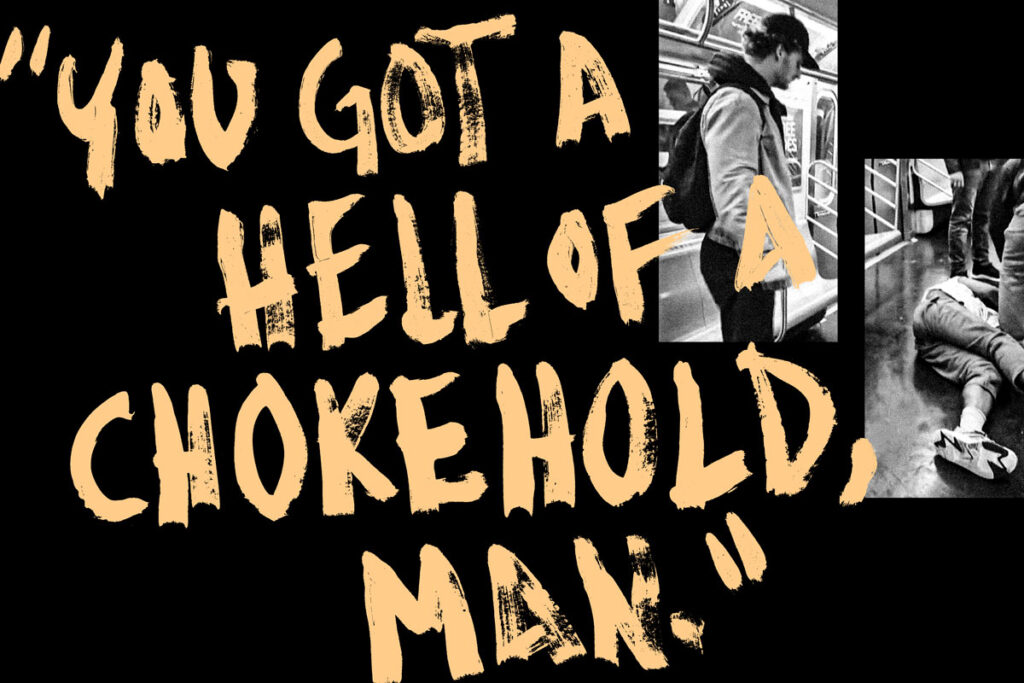

How is it that a disciplined infantryman in the United States Marines applied a blundering, lethal chokehold to the distraught Neely? Why did he ignore the warnings of a bystander that he might “catch a murder charge” if he kept up with his “hell of a chokehold”? Why, in an era of military operations officially characterized by counterinsurgency nation-building, “winning hearts and minds,” and de-escalation, did the marine choose to assail a troubled homeless man in the first place?

The background of the killer’s legal counsel may also raise eyebrows: a defense attorney foraying into electoral politics as a tough-on-crime crusader; an opponent of bail reform rushing to the protection of a vigilante who, after killing an agitated but nonviolent street performer by choking him from behind, was released by the cops without further ado; a lawyer inspired to practice law by a film indicting the very hazing-inflected masculinity and extrajudicial violence embodied by his latest customer, who isn’t so much a lowly antihero as the all-American hero gone berserk.

As the journalist David Klion has noted, the hero in question was raised in a million-dollar residence in West Islip, a Long Island town with a household income forty percent greater than the New York state median. West Islip is so white (96 percent) that some call it “White Islip.”

Although his lawyers take on low-income defendants, they also have considerable experience as prosecutors and attorneys for large corporations, and they specialize in defending those accused of sex-based discrimination under Title IX. Kenniff sits on the board of Operation: Heal Our Heroes, a charity devoted to treating the trauma of veterans. Although judging by their political involvements and donations, it is more than plausible such philanthropy is motivated, in no small part, by the boilerplate nationalism so prevalent among today’s conservatives.

According to the reporter Talia Jane, Neely’s killer himself has since 2016 been an active registrant of the Conservative Party of New York State, a third party that has over the past seventy years aimed, often successfully, to nudge the state’s GOP further to the right.

The killer and his legal team believe the world is meant to be policed by a certain type of hero, whether in uniform or not, in Baghdad or New York. And it is that hero’s worldview, shot through with erratic, racist instincts and an equally erratic class contempt, that helps resolve any ostensible ambiguities. To be this kind of hero no longer requires being white or rich (at least one of those assisting the killer in his killing was not white, and possibly not rich). It doesn’t even require being disciplined or law-abiding. But it does require an unflinching commitment to the racial and class order the law upholds. A system that typically ensures those on its wrong end look more like Jordan Neely or William Santiago than their whiter, richer counterparts. And a system forever enforced, in their minds, by a few good men.

Only Thomas Kenniff knows what it was about Tom Cruise in A Few Good Men that sparked his decision to become a military lawyer. But if the writer Anthony Swofford is right that all antiwar films are pro-war, then it is just as true that all movies critical of the military are still pro-military. It is doubtful Kenniff picked up on the critique animating the classic blockbuster. Namely, that Cruise’s character can only bring honor to the military through his dissent from the established hierarchy and his compassion for the murdered outcast Santiago. (Of course, the character’s easy moral victory depends on the notion that the law—and the U.S. Uniform Code of Military Justice—is designed to protect the weak and the persecuted, a notion that runs counter to all available evidence but nonetheless fulfills Swofford’s premise.) Kenniff probably just wanted to be a celebrated patriot like the one Cruise personified.

Likewise, only Kenniff’s client can know why he became a grunt, and why, after his discharge, he strangled Neely to death. But one doesn’t need to be a naif to believe that Penny might have thought he was in earnest when he wrote on a job site that being a marine made him realize he “loved helping, communicating, and connecting to different people from all over the world.”

In all likelihood, even the cops who released the killer tell themselves they, too, want to be the good guys. Or at some point, anyway, they each sought to become one of the few good men.

Except everything about their acculturation makes a mockery of that ideal. Because it’s predicated on administering, often by deadly force, a rotten pecking order. An order that is implied in the motto itself, where only a few get to be good. And where everyone else is their prey.

Neely’s killer was an active duty marine from 2017 to 2021, meaning his service paralleled the presidency of Donald Trump. An easy takeaway would be that his behavior on May 1 encapsulates that political moment, a moment when the worst impulses of comfortable white men—along with their fans—were unleashed to the max.

But this reality has both preceded and outlived the Trump presidency. Throughout the bipartisan War on Terror, the Marines tolerated perfunctory hip-pocket classes on de-escalation or cultural sensitivity. But the heart of the indoctrination was typified by chants of “Kill kill kill Hajji!” during bayonet training or little ditties about raping babies and grandmothers during the early morning run. The famous words of General Jim Mattis, the most beloved Marine icon of the era, had long been emblazoned on plaques across the Corps: “Be polite, be professional, but have a plan to kill everyone you meet.”

Something akin to this mentality was drilled into many of the rank and file in the other branches, too. And one mustn’t neglect the overriding mindset of their domestic equivalents—the men (and sometimes women) in blue. Armed with military surplus equipment, many themselves veterans—according to the DOJ, some 25 percent of American law enforcement have a military background—the nation’s police forces have pursued the “war on drugs” alongside the War on Terror and using many of the same tactics.

Illustration by Lindsay Ballant/The Forum. Former Marine Daniel Penny is seen on video, recorded by freelance journalist Juan Alberto Vázquez, placing Jordan Neely in a fatal chokehold on the New York City subway on May 1, 2023. Penny is charged with with manslaughter in Neely’s death. The extended video, obtained by the Daily Mail days after the incident, shows Penny appearing to ignore another subway passenger who warned “You’re going to kill him” while Penny had Neely in a chokehold for nearly fifteen minutes.

Understanding the integral relation between the warriors at home and abroad is crucial to understanding the war. So is understanding how this war’s apologists are constantly flipping upside down hierarchies of race and capital, and moral universes altogether. Where the slightest aggressions of the dominated get sold as existential threats, and the regular, disproportionate death-dealing of status quo devotees is marketed as noble necessity.

After Neely’s killer turned himself into authorities, received a second degree manslaughter charge, and was released on bail, Florida governor Ron DeSantis tweeted:

We must defeat the Soros-Funded DAs, stop the Left’s pro-criminal agenda, and take back the streets of law abiding citizens. We stand with Good Samaritans like Daniel Penny. Let’s show this Marine . . . America’s got his back.

DeSantis encouraged his followers to contribute to the killer’s legal defense fund, an effort reminiscent of the right rallying behind Kyle Rittenhouse, who shot three men, killing two, during protests against the police shooting of Jacob Blake in Kenosha, Wisconsin. Yet DeSantis himself is a former JAG officer credibly accused of complicity in suspicious deaths and abuse at the Guantanamo Bay detention camp. So his rhetoric supporting Penny’s actions should also call to mind Trump’s pardons of arraigned war criminals like Eddie Gallagher and Mathew Golsteyn, or further back, chauvinist support for Lieutenant William Laws Calley after the My Lai massacre.

When you’re the eternal good guys, it’s remarkable all the bad things you can get away with doing. Here or anywhere. Plain-clothed or uniformed. The gap between the virtuous mythology and vicious actuality keeps expanding, just like your imperial birthright.

The point isn’t that the nation’s warfighters and cops (or their lawyers) are monsters. Most—again—set out to do good. Be good. Some even achieve some goodness every now or then. In their personal lives. Even on the job.

The point is simply that the machinery they maintain is monstrous. According to the Costs of War Project at Brown University, America’s post-9/11 wars have killed over 929,000 people in direct violence, and at least 4.5 million indirectly through overall illness, infrastructural breakdown, and regional instability. Millions more have been severely wounded, rendered penurious, familyless, or without shelter. Whole nations and life-worlds have been destroyed, only to be replaced by more oppressive blowbacks, as we’ve seen increasingly across Africa.

For Americans, all of this has taken place as if it hasn’t taken place at all. Its narration is left to its surviving victims and a miniscule coterie of journalists, researchers, politicians, and artists in the United States who care to elevate them. Many haunting books, like the poet and novelist Sinan Antoon’s The Book of Collateral Damage, have been written on the subject. Yet few Americans have chosen to read them.

And it is no coincidence that these millions of unspoken destructions have taken place among people darker-skinned than the subway killer. And in much poorer parts of the world.

For a fleeting interval, Americans spoke openly about related horrors at home. They learned that the United States led the world in incarceration rates, surpassing the most authoritarian regimes on the planet. They learned that despite a steady decline in crime over the past few decades, the number of those being imprisoned has increased fourfold the past half century. That the poor are three times as likely to be arrested, and the extremely poor fifteen times more likely to end up with a felony charge. That Latino or Latina people are almost three times more likely to be incarcerated, and black people almost six times more likely.

Mainstream television and radio guests discussed how policing is designed to manage the surplus populations of the unemployed or under-employed. How these heavily racialized populations wouldn’t be forced into poverty or captivity were egalitarian outcomes—rather than elite gains—the ultimate objective. How just like the military-industrial complex, the carceral state produces shocking upward redistributions (and morbid redirections) of wealth and power, as well as the further erosion of liberal democratic norms—never mind any hopes for genuine social or economic democracy.

Yet since Americans, and the media celebrities who curate their opinions, were unwilling to give up on the presumption of American virtue (and their faith in America’s armed guardians), many forgot these hard lessons amid a sea of reports of increasing lawlessness in the wake of the pandemic.

Hence, on May 1 of 2023, there was little space devoted to the promising legacies of International Workers’ Day. And seemingly infinite airtime and column inches debating whether it was understandable to choke to death a discomposed man in hungry destitution. For declaring his sad state while throwing trash toward passengers and his jacket on the subway floor.

The man who killed Jordan Neely was a marine. And this shouldn’t surprise us.

Americans in (or formerly in) the military commit violent crime at rates far higher than civilians. Active-duty members are three times more likely to perpetrate domestic violence. A chilling 28.5 percent of mass shooters have backgrounds in the armed services. Twenty percent of those charged in the January 6 riot on the capital were military or former military.

Statistics on cops—including the cops who released Neely’s killer—aren’t all that different. This shouldn’t be surprising either. And not just because uniformed personnel endure high rates of post-traumatic stress and traumatic brain injury. The trauma explanation is real but incomplete. Most people who experience trauma, or even suffer TBI, are not violent. The operative factor is the training to recycle their traumas through violence. And this is precisely what U.S. militarism and the carceral state do.

The truth is America’s few good men are trained primarily to kill. Some have already killed or helped others in the killing—sometimes, like Penny, in a matter of seconds, at other times more gradually, through every dehumanizing measure short of causing instantaneous death. And they’ve been worshipped for doing so by a society that hasn’t begun to reckon with the far-reaching consequences of its jingoistic institutions.

These are truths too many Americans still can’t handle. They would rather go on refusing to imagine the myriad nonlethal possibilities available to all of us, nearly all of the time. Given how much demagogues—in both parties—profit off this refusal, this should be no surprise, either. Our political leaders put a massive amount of energy into dismissing any attempt at de-escalatory prudence or long-term social investments as impractical. This is reflected in New York City mayor Eric Adams’s cynical use of Neely’s murder to promote his carceral mental health policies—asserting that Neely should have been forcibly committed for his own safety, all the while refusing to pass judgment on his killer, and calling those who condemned Penny or demanded criminal charges “irresponsible.”

When a nation is at perpetual war, it becomes easy, inevitable even, for brutality to become the first resort rather than last, and in an ever-widening list of circumstances. At least, this brutality becomes easy for a subset of Americans—those we are told exist for us, “to protect and serve” our communities and nation, but in truth, those for whom we are supposed to exist. Toiling so that wealth can be redistributed upward. Cast into unemployment and homelessness so that inflation can be tempered and markets stabilized. Obeying their commands so that racial and class hierarchies can be maintained. They aren’t so much above the law as they are the law itself. The order they uphold might, in some structural sense, come from on high. But that order hails just as much from within themselves, from the deep-set belief that they are the few good men tasked with regulating (sometimes killing) the rest.

They call their order the rule of law. Western values. Civilization. While everyone else, particularly people like Jordan Neely, are forced to acknowledge their order’s true character.